Blue Cliff Record, Case 2

Chao-chou, teaching the assembly, said, “The Ultimate Path is without difficulty; just avoid picking and choosing. As soon as there are words spoken, ‘this is picking and choosing, this is clarity.’ This old monk does not abide within clarity; do you still preserve anything or not?”

At that time a certain monk asked, “Since you do not abide within clarity, what do you preserve?”

Chao-chou replied, “I don’t know either.”

The monk said, “Since you don’t know, Teacher, why do you nevertheless say that you do not abide within clarity?”

Chao-chou said, “It is enough to ask about the matter; bow and withdraw.”

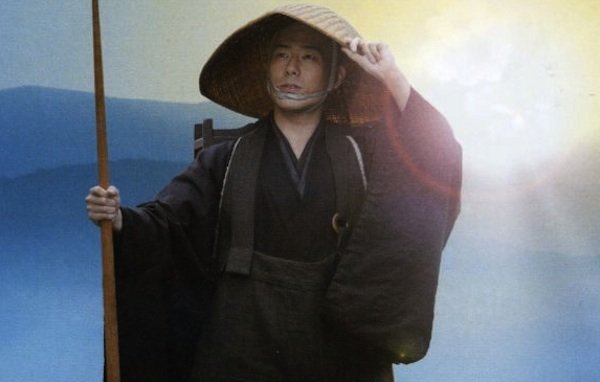

Chao Chou, also known as Joshu, is among the most esteemed and frequently-quoted ancestors of Chinese Zen, and was much beloved by one of Treetop’s founding teachers, Stef Barragato. He appears numerous times in the major koan collections, including the famous “mu” koan, Case 1 of the Gateless Gate. That case, which our teacher Peter Wohl has called “the great Pac-Man of the ego,” is often the first question given to new students to wrestle with at other practice centers.

This particular case is one of a set of four similar cases collected in the Blue Cliff Record. In addition to this case, we have …

Case 57: A monk asked Chao-chou, “‘The Ultimate Path has no difficulties—just avoid picking and choosing.’ What is not picking and choosing?”

Chao-chou said, “‘In the heavens and on earth I alone am the Honored One.’”

The monk said, “This is still picking and choosing.”

Chao-chou said, “Stupid oaf! Where is the picking and choosing?”

The monk was speechless.

Then Case 58: A monk asked Chao-chou, “‘The Ultimate Path has no difficulties—just avoid picking and choosing’—isn’t this a cliché for people of these times?”

Chao-chou said, “Once someone asked me, and I really couldn’t explain for five years.”

And finally, Case 59: A monk asked Chao-chou, “‘The Ultimate Path has no difficulties—just avoid picking and choosing. As soon as there are words and speech, this is picking and choosing.’ So how do you help people, Teacher?”

Chao-chou said, “Why don’t you quote this saying in full?” The monk said, “I only remember up to here.”

Chao-chou said, “It’s like this: ‘The Ultimate Path has no difficulties—just avoid picking and choosing.’”

While Chao Chou has been so often quoted himself, this particular saying he was so fond of was not original to him. It’s a quotation from “On Trust in the Heart,” a poem by the Third Patriarch of Zen in China, Jianzhi Sengcan. The poem, which appears in our service books, and which some of us spent time studying this winter, begins, “The perfect way is only difficult for those who pick and choose. Do not like, do not dislike; all will then be clear. Make a hairbreadth difference and heaven and earth are set apart; if you want the truth to stand clear before you, never be for or against. The struggle between for and against is the mind’s worst disease …”

One of the first Zen teachers I ever met once told me that she began practicing to find peace of mind. In this world where the law of impermanence leaves nothing untouched, she said, “If your peace of mind depends on your loved ones not dying, or you not dying, you’re in trouble.” True peace, she told me, is not dependent on external conditions.

This concept was not unique to her. We can see it right in Shakyamuni Buddha’s Four Noble Truths, the first and most basic teachings he offered after his enlightenment experience under the Bodhi tree.

They are, First: There is dukkha, that is discomfort and discontent, or as some translate it, suffering. We never have enough of what we want; we jealously guard what we do have, desperately, futilely, trying to keep it; and we’re always getting more and more of what we don’t want.

Second: The cause of that discomfort and discontent is our own clinging and aversion.

Third: There is a way out of this discomfort and discontent. We don’t have to endure it forever.

Fourth: That way out is to ardently train our minds to let go of our clinging and aversion by practicing the Buddha’s Eightfold Path.

In other words, “Do not like. Do not dislike. All will then be clear.”

That promise, that we can be free from suffering, is Buddhism’s major draw. It’s so simple, and yet sounds too good to be true, as though Shakyamuni took a marketing class from Zig Ziglar. “Be free from suffering in eight simple steps! No money down! Act now!” Who wouldn’t want to at least look into it?

When I was new to Zen practice, though, as compelling as this idea was, I also felt some unease with it. Let go of my preferences? And then what? Let the world descend into chaos? Wash my hands of my commitment to social justice, of my heartfelt desire to see an end to poverty, war, sexism, racial inequality, or the rape of our planet? So what if children in developing countries—hell, kids in our own country—are eating garbage or breathing in toxic fumes. As long as I have inner peace, that’s all that matters.

My feelings echoed the words of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., “There are certain things in our nation and in the world (to) which I am proud to be maladjusted.” If starting down the Buddha’s Path meant not caring—if it meant learning to become adjusted to horror—I wasn’t sure I wanted any part of it.

And, indeed, there have been Buddhists throughout history who succumbed to just such pernicious quietism, of retreating from the world and refusing to sully their hands with material concerns. But, to my thinking, this interpretation of the teachings misses the mark.

Environmental activist, author, and Buddhist scholar Joanna Macy hit upon this very difficulty in a recent address to the Buddhist Peace Fellowship. “Western Buddhists are very suspicious of attachment,” she said, “They feel they need to be detached, so don’t get upset about racism, or injustice, or the poison in the rivers, because that means you’re too attached. This causes some difficulty for me, because I’m attached. I think one of the problems with Westernized Buddhists is premature equanimity. When the Buddha said ‘don’t be attached,’ he meant don’t be attached to the ego.”

Macy and the members of the BPF she was addressing represent a movement called Engaged Buddhism, Buddhist practitioners who, prompted by teachings on compassion and the direct realization that all beings are inextricably interconnected, engage in social action as a form of practice. To me, that’s just as it should be. To steal a line from Peter Wohl, “Engaged Buddhism is redundant.” To practice the Buddha Way is to be engaged, intimately, with the world and all of its suffering beings.

I cringe when I hear people describe the aim of Buddhism as “detachment.” I prefer to term “non-attachment,” because, to me, it doesn’t conjure the same connotations of being aloof or disinterested—of being “checked out”—that detachment does. Waking up is not about checking out. It’s about checking in, fearlessly facing what’s in front of us without denial, without our habitual storylines, and without retreating to the safety of our fantasy worlds or our addictions.

I once read an article about people who’d survived plane crashes. The premise of the article was that the people most likely to survive a life-threatening emergency, such as a plane crash, are those who are best able to accept the reality of what happened to them. Survivor after survivor told stories of others who’d also escaped the immediate impact with their lives only to fall apart in the crucial hours afterward because they were unable to process and integrate the new, ugly, painful post-crash reality they now inhabited. Those people, clinging desperately to a fictional world in which they’d arrived at their destinations with no more than a case of indigestion from lousy airline food, were unequipped to face the challenges that remained in front of them.

It’s not that those who did survive felt no emotions about their situation, or that they sat placidly, in perfect samadhi, amidst the twisted wreckage that had, not long before, been sailing gracefully through the sky above. I’d bet that not one of those people was “detached.” Each of them fought tooth and nail against adversity—injury, illness, exposure, hunger, thirst, and fear of never being found—doing whatever needed to be done to ensure their survival. Pushing aside the inevitable despair and self-pity that each of us is so familiar with at times, they kept their heads clear and their eyes on dealing with whatever necessity was in front of them, finding water or shelter, seeking a way out or signaling for rescue. Instead of panicking, they simply did the next thing that needed to be done until they were safe.

This metaphor can easily be extended to any situation we find ourselves in. Whether we’re trying to overcome an addiction or a neurotic tendency, achieve some health goal, or we’re standing up to confront environmental devastation or systemic oppression, we must start from a place of what Insight Meditation teacher Tara Brach calls “radical acceptance.”

Letting go of like and dislike means we don’t wait for some ideal future situation to begin working toward the change we want to see in the world, or in ourselves. Because that future never comes. We only ever have right now, so we have to start from who and where we are. Like a good doctor, if we want to heal ourselves, our fellow beings, and our world, we have to start by looking deeply at and acknowledging the sickness and its causes. A doctor doesn’t wait until the patient is well to begin healing her. As paradoxical as it may seem, if we want to bring about what could be, we must begin by embracing and accepting what is. If we try to push painful realities away, to separate from them, to retreat into the comfortable certainty of our likes and dislikes, we’ll never be able to see clearly what needs to be done. Our egos will be in the way.

Radical acceptance doesn’t mean we give up on improving ourselves or our world. It doesn’t mean we decide everything is fine just the way it is, so let’s open another box of Twinkies and binge-watch the next season of our favorite Netflix show. And it certainly doesn’t mean we’re free to float in eternal bliss on a lotus petal in some Heavenly Being realm we’ve created in our own minds, either.

Enlightenment is not a state we reach, once and for all. Enlightenment is a daily vow, a daily struggle, to maintain equanimity even in the midst of the joys and sorrows of our fragile human existence—even when our hearts are broken, and they will break if we’re paying attention—and to use that equanimity to help us work for the benefit of all beings.

This is what Chao Chou meant when he said he doesn’t abide within clarity. To do so would mean clinging to an idealized state called “clarity” instead of being present right here and now. This open, accepting state of mind is often referred to by Zen teachers, ancient and modern, as “not knowing.” Far from the “not knowing” of ignorance, this “not knowing” means letting go of what we think we know—of what our grasping, clinging egos think we or others need—and attending to what is.

It doesn’t mean we can’t use the wisdom we’ve gained from experience. And it doesn’t mean we don’t have preferences. As long as we are human beings who live and breathe, we will always have preferences. I, for one, have a strong preference for breathing. It just means we’re not hemmed in by what we know or what we want. It means we stay open to possibilities and present to reality, even when things don’t go quite how we think they should.

Like those plane crash survivors, Zen practitioners don’t need to abide in a fantasy world, pretending everything is OK, even as the sky is literally falling. We simply do the next right thing, one step after another, tending to whatever needs to be tended to, and dropping whatever weighs us down.

Chao-chou, teaching the assembly, said, “The Ultimate Path is without difficulty; just avoid picking and choosing. As soon as there are words spoken, ‘this is picking and choosing, this is clarity.’ This old monk does not abide within clarity; do you still preserve anything or not?”

At that time a certain monk asked, “Since you do not abide within clarity, what do you preserve?”

Chao-chou replied, “I don’t know either.”

The monk said, “Since you don’t know, Teacher, why do you nevertheless say that you do not abide within clarity?”

Chao-chou said, “It is enough to ask about the matter; bow and withdraw.”