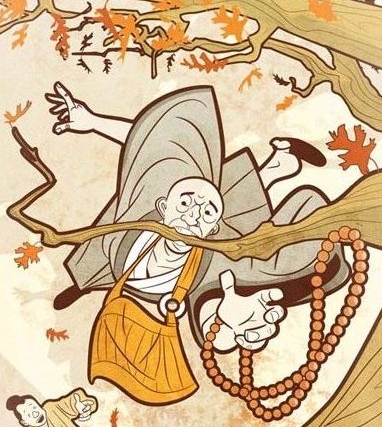

Blue Cliff Record, Case 89

Yunyan asked Daowu, “How does the Bodhisattva of Great Compassion use so many hands and eyes?”

Daowu said, “It’s just like a person in the middle of the night reaching in search of a pillow.”

Yunyan said, “I understand.”

Daowu said, “How do you understand it?

Yunyan said, “All over the body are hands and eyes.”

Daowu said, “What you said is all right, but it’s only eighty percent of it.”

Yunyan said, “I’m like this, elder brother. How do you understand it?”

Daowu said, “Throughout the body are hands and eyes.”

I have heard that the current Chinese government fears and represses the Taoists, because over the course of that country’s history they have periodically emerged from the mountains and led populist revolts against the ruling regime. History has shown that when they decide to act, they are a force to be reckoned with. On the other hand, Buddhists in China currently face much less repression because their history has been passive; they have no record of emerging from their monasteries to lead the people toward political change.

In a sense, that is our heritage as Buddhists, one of political quietism, in spite of some notable exceptions in recent times, such as in Vietnam and Myanmar. It appears that there are several broadly held perspectives within the contemporary American Buddhist community that support this basic tendency to eschew political and social controversy.

The first of these is the idea that the affairs of this world are unimportant, that a higher spiritual plane, that of the Absolute or Emptiness, is the true reality and that, dwelling there, we are freed from suffering in this life. A similar, more contemporary, idea is that we practice in order to live exclusively in the present moment, to be “mindful,” and therefore personally liberated, calm, and free from stress and strife.

Zen is a Mahayana practice, though. As such, it isn’t aimed at dwelling in the Absolute, living in Nirvana. Zen talks about the relative and the absolute as being one, a fully integrated reality. As Shitou Xiqian reminds us in The Sandokai, “to encounter the absolute is not yet enlightenment.” In the final stages of practice, we must lose our attachment to the Absolute, using our realization to inform our actions as we enter the marketplace to deal with the often difficult, messy, and painful actualities of this world of Samsara.

The Mahayana goal is to save all beings. This is actualized through the Bodhisattva archetype, which is that of a person who gives up their own place in Nirvana to return to this world for the sake of all beings. One way to understand this is not in the context of actual death and rebirth, but rather in the sense that we constantly need to relinquish Nirvana, defined as the blissful state that is experienced when residing in the Absolute. Instead, the Bodhisattva continually returns to the world of Samsara for the sake of other beings. We must be reborn in each moment.

A second reason for avoiding social/political action is the idea that enlightenment, or deep spiritual awakening, should be a prerequisite for taking action. Until we have had that experience, some argue, we should focus solely, single-pointedly on our practice. This viewpoint is based on several misapprehensions, the foremost of which is that enlightenment is an actual object, a discrete, observable, constant “thing” that appears at some moment in a person’s life.

Perhaps this mistaken belief is fueled by accounts of very dramatic, sudden kensho experiences, such as those published in Philip Kapleau’s Three Pillars of Zen, a foundational text for many Western practitioners. Firstly, while such experiences do occur, for most people the process is not that dramatic. Rather, realization occurs as a succession of openings, each helping to gradually deepen the person’s awareness. Secondly, referring again to Shitou Xiqian’s statement that encountering the absolute is not yet enlightenment, even when an earth-shaking sudden kensho does occur, many years of practice remain before that experience is fully integrated into the person’s life. And even then it remains a practice of moment to moment awareness to sustain the open, realized state.

I believe it is most accurate to say that one is never enlightened, but that enlightenment is something that we aspire towards as we practice throughout our lifetime, awakening again and again in each moment. It is not a constant state that we can reach and reside in, if we are to fulfill our Bodhisattva vows. Rather than remaining aloof, we must engage intimately with the suffering of this world. If we are waiting for enlightenment as a prerequisite for action, we will allow the possibilities of a lifetime to pass us by.

A third reason often given for avoiding action is that, by simply sitting and saving ourselves, we are in fact changing the world, and therefore we should invest all of our energy there. I do not dispute the first part of that belief. This is truly One Body, and therefore our lives do matter, our awakening does change the entire universe. Nor do I take complete exception to the second part of that idea. Awakening does take a powerful single-pointed effort. But I don’t agree that needs to supersede everything in our lives. While we need to apply assiduous effort in both our daily practice of zazen and in the intense environment of sesshins, we should also invest ourselves wholeheartedly and without hesitation in the rest of our lives. That, too, is practice; that, too, is Zen. If fact, for those of us who are householders, Zen practice cannot take precedence, if we are to maintain balance, in our complex multi-dimensional lives.

Still, from the first time we sit down on the cushions we get glimpses of clarity, moments of less self-centered, more open awareness. Regardless of how long we have practiced, or whether we believe ourselves to be “enlightened” or not, those times of clear insight need to become the basis for action. As we sit here today, we are in the sixth era of species extinction, a time when more species are disappearing from the Earth than in the time of the dinosaurs. This is truly an emergency of epic proportions, especially since the vast majority of these extinctions are the result of human activity.

Additional consequences of that activity are the rapidly shifting climate as carbon dioxide emissions rise, the depletion of the ozone layer, large scale processes of deforestation and desertification, nuclear accidents, global resource depletion, and so on… Never before has all life on Earth been in such jeopardy. This is further compounded by the fact that competition for dwindling resources is resulting in human conflicts. Blood is being shed for oil, but that may be nothing compared to the future conflicts as not just oil, but also Earth’s water supplies, vanish.

I would argue that as Zen practitioners we must act as the koan says, “like reaching for the pillow in the middle of the night.” When the pillow slips away we don’t stop and think, “I must remain focused on the Absolute, I am not concerned with the unimportant fact that my head is uncomfortable.” Neither do we wonder whether we are enlightened enough to reach for the pillow or imagine that, because we sat zazen that day, the world has changed and pillows are no longer necessary. We act completely reflexively. There is no thought; we just reach out and stuff the pillow back under our heads.

That is a description of the action of compassion. True compassion is spontaneous, natural, and comes from a deep place of “not knowing.” In the Zen Peacemaker Order, there is a simple template for Buddhists to follow in taking action, which has three parts. Not knowing is the first of these, followed by bearing witness and loving action. Not knowing means just that, letting go off all that we think we know about a situation, including our conceptions, our preconceptions, our beliefs about right and wrong, and most importantly, the very idea of separation. We enter the situation completely open and unfettered, and therefore able to respond as the situation requires.

Secondly, we bear witness. This is an extremely powerful way to interact with the realities suffering, destruction, violence and death. In bearing witness, we sustain our gaze. We hold the intimate space open, refusing to close our eyes, turn away, or to use psychological mechanisms to protect and distance ourselves. In this case, we must not allow ourselves to be diverted by despair. We cannot simply say, “The problems are too big, there is nothing I can do.” It may sound trite, but every day we are either part of the problem or part of the solution. If we face the source of our despair directly, we don’t allow it to rob us of our power. Remarkable things can begin to happen when we allow this direct encounter to happen.

Finally, we act with lovingkindness. In this case, it is necessary that we interact with the world, Gaia, in such a manner that we treat the great Earth itself, as well as all beings within this vast, pulsing, living organism, with love and kindness. Simply, as in the perspective of the Deep Ecology movement, we must consider the well-being of the entire biotic community as part our self, rather than viewing it through the lens of our narrowly defined human needs. We must not only do this in our major resource allocation decisions, but in even the minutest aspects of our daily lives. That means we cannot live in a dream state, acting blindly, unaware of the consequences. We must awaken in every minute, open into not knowing, bearing witness to the deep realities of our actions and their consequences, and allowing this realization to give birth to clear, decisive, loving action on behalf of the world.

When our minds are in the right condition, it is very, very simple, like reaching for the pillow in the middle of the night! Practice is the hard work of bringing our minds into that condition, again and again.

Photo by Andrew Marino. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.