Book of Serenity, Case 20

Book of Serenity, Case 20

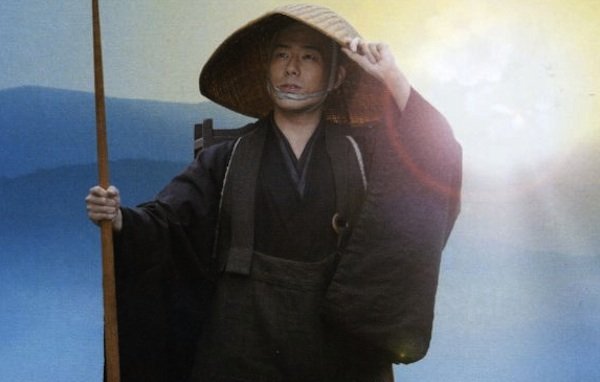

Fayan was going on pilgrimage.

Dizang said, “Where are you going?”

Fayan said, “Around on pilgrimage.”

Dizang said, “What is the purpose of pilgrimage?”

Fayan said: “I don’t know.”

Dizang said, “Not knowing is most intimate.”

Anyone who’s ever spent a lot of time with small children has likely played the “why” game.

When we’re kids, everything in the world is new and mysterious, and we want to know why things are the way they are. Everything we encounter is an opportunity for discovery.

“Why is the sky blue?” a child might ask.

If we paid attention in high school science, we might answer that the sky is blue because the gas molecules in the air scatter blue light from the sun more readily than they scatter red light.

“But why?”

Well, because each color in the spectrum has a different wavelength, and blue light travels in shorter, smaller waves than red light.

“But why?”

If we have a deeper level of scientific understanding than the average person, we may be able to answer subsequent layers of whys, but, as useful and important as scientific knowledge of the world is, there will eventually be a “why” that brings us up short.

The place where humanity reaches the limits of our collective scientific understanding is where the realms of metaphysics and theology take over.

To a person of a theistic bent, coming against the barrier of human understanding seems like no problem. A person of faith will simply answer that next “why”— or maybe even the very first one—by saying, “Because God made it that way.”

But if the inquisitive child is undeterred and again asks why, then what can we say?

And what about all of those more urgent, nagging questions that are usually the purview of theologians?

Why is there so much misery in the world? Why do bad things happen to good people? Why is there cancer? Why is there addiction? Why are there people starving or sleeping on the streets when we have enough resources for everyone? What happens when we die?

Is there any answer except the one the mystics of old gave—“It’s a mystery”— that could be anything more than pure speculation, an arrogant attempt at making God in our own image? Is there any answer anyone could give that could possibly satiate that inner longing for understanding?

Many of us came to Zen precisely because we were unsatisfied with the pat answers to these questions and others we’d so often heard, because we had some sense that there had to be deeper answers to the big questions in life.

But Buddhism is unique among the world’s religious traditions in that it makes no such attempts to provide answers to the great metaphysical questions, at least not in the way we’re accustomed to.

It’s true that the Buddha made use of the common cosmological understandings of his time and place to explain his teachings. He lived in a cultural context that looked at the world through a Hindu set of lenses, and so he made use of imagery his audience would understand, while also turning many of the central tenets of that spiritual tradition on their heads. I’ve often thought that if the Buddha had been born in Medieval Europe, he’d have used Christian archetypes to explain his teachings, and if he’d come in the modern era, he may well have used scientific, industrial, or even digital, metaphors.

But the cultural trappings of early Buddhist teaching—rebirth, gods, fighting spirits, hell realms, hungry ghosts—were merely a backdrop to help him explain his insights and show others the way out of suffering. They were not at all central to his message.

In fact, over and over again, when people asked the Buddha metaphysical questions about the nature of the universe or the soul, he refused to answer. Instead, he told the following parable.

“It’s just as if a man were wounded with an arrow thickly smeared with poison. As if his friends and companions, kinsmen and relatives provided him with a surgeon, and the man were to say, ‘I won’t have this arrow removed until I know whether the man who wounded me was a noble warrior, a priest, a merchant, or a worker.’

Or if he were to say, ‘I won’t have this arrow removed until I know the given name and clan name of the man who wounded me… until I know whether he was tall, medium, or short… until I know whether he was dark, ruddy-brown, or golden-colored… until I know his home village, town, or city… until I know whether the bow with which I was wounded was a long bow or a crossbow… until I know whether the bowstring from which I was wounded was fiber, bamboo threads, sinew, hemp, or bark… until I know whether the shaft by which I was wounded was wild or cultivated… until I know whether the feathers of the shaft with which I was wounded were those of a vulture, a stork, a hawk, a peacock, or another bird… until I know whether the shaft with which I was wounded was bound with the sinew of an ox, a water buffalo, a langur, or a monkey.’”

It goes on and on like this …

“The man would die and those things would still remain unknown to him.”

As absurd as that story sounds, the irony is that each and every one of us is that man. We are each walking around with a poisoned arrow sticking out of our chests. It’s called impermanence. We are all subject to the ravages of suffering, old age, and death, and our frantic attempts to escape them through denial, anger and depression, or bargaining, are of no use. There is no escape. There can only be acceptance.

No matter how much kale we eat, how many vitamins or turmeric supplements we take, how many facelifts we get, how many flashy sports cars we buy, or how fervently we pray, impermanence stalks us all. And it has much more stamina than we do. Impermanence is tireless.

Most of us here, know that, of course. That’s why we’re here. And, true to our expectations, Zen practice gives us plenty for our restless, searching minds to wrestle with. Not only do we have our own questions, but we get handed more in the form of koans.

“Count the stars.”

“Why is there no cat in the painting of the Last Supper?”

“Why did Bodhidharma come from the West?”

“What is the sound of one hand?”

“Does a dog have Buddha Nature?”

We jump in thinking we’ll finally learn the secrets we’ve been missing all along, but as long as we persist in trying to make sense of things, in trying to fit everything into our narrowly defined constructs, we’ll continue banging our heads against a brick wall.

Life can’t be understood. It can only be lived.

This practice is designed to short-circuit our habitual pattern of intellectualizing, philosophizing, rationalizing, minimizing, and generally separating from the reality of our lives by retreating into the comfort and security of our thoughts.

Every attempt to answer through logic, every attempt to explain, to pontificate, to demystify, is rebuffed. No, that’s not it, we’re told. Go deeper, we’re told, until we’re left empty-handed, unprotected.

This is vividly illustrated in another koan featuring Fayan, which appears in the Blue Cliff Record. This story took place a long time after his encounter with Dizang, once Fayan had become a teacher with a monastery of his own.

Superintendent Tse had been staying in Fayan’s congregation, but had never asked to enter his room for special instruction. One day Fayan asked him, “Why haven’t you come to enter my room?”

Tse replied, “Didn’t you know, Teacher, when I was at Ch’ing Lin’s place, I had an entry.”

Fayan said, “Try to recall it for me.”

Tse said, “I asked, ‘What is Buddha?’ Lin said, ‘The Fire God comes looking for fire.”‘

Fayan said, “Good words, but I’m afraid you misunderstood. Can you say something more for me?”

Tse said, “The Fire God is in the province of fire; he is seeking fire with fire. Likewise, I am Buddha, yet I went on searching for Buddha.”

Fayan said, “Sure enough, the Superintendent has misunderstood.” Containing his anger, Tse left the monastery and went off across the river. Fayan said, “This man can be saved if he comes back; if he doesn’t return, he can’t be saved.”

Out on the road, Tse thought to himself, “He is the teacher of five hundred people; how could he deceive me?” So he turned back and again called on Fayan, who told him, “Just ask me and I’ll answer you.” Thereupon Tse asked, “What is Buddha?”

Fayan said, “The Fire God comes looking for fire.”

At these words Tse was greatly enlightened.

Koans are not metaphors we can unpack, and neither are our lives. There is no decoder ring we need to find. No cipher we need to unlock. All the explanation we need is right here, just waiting for us to stop hiding, stop hedging, stop trying to impress, and stop withholding the most protected corners of our hearts for fear of being hurt or humiliated.

When that finally happens, when we finally get tired of our own noise, the result is utterly ordinary, and yet no less miraculous for it.

The result is intimacy.

You’ve heard it said that familiarity breeds contempt. Even if that’s not exactly true, it certainly grants us the license to check out, phone it in, and coast along based on deeply ingrained assumptions.

Have you ever driven somewhere you’ve been million times before—work, maybe, or the grocery store—and realized once you’d arrived that you have no recollection of your trip there? Or perhaps you’ve gone to complete some routine task only to find that it had already been completed despite your having no recollection of having done it.

It sounds dysfunctional to say it out loud like that, but these kinds of lapses happen all the time. Too much of the time, we go through our lives habitually checked out, in a dreamlike state. This is why the Buddha described his insight under the Bodhi tree as an awakening.

When we’re in truly new territory, though, we become like kids again. Not knowing shows up in the form of curiosity and wonder. We pay close attention. That’s why people who’ve experienced life-threatening situations describe a sense of time slowing down or standing still. Novelty jars us out of our daze and forces us to switch out of autopilot mode.

“Not knowing” does not mean we must reject conventional knowledge. There is value in learning about our world. But we must be careful not to let our knowledge stand in as a proxy for intimacy.

Even if we could tie up all of our questions into neat ideological bows, the answers wouldn’t help us. All the messiness and immediacy of our lives would still be there, waiting for us on the other side.

We could spend our lives immersed in learning about the reproductive cycle and the genetic code, but it wouldn’t compare to the experience of holding a child in our arms, of looking down at that wild, warm, breathing little creature and knowing it came from you.

And all of the available scientific knowledge about what causes cancer and how it spreads won’t prepare us to for how it feels to hear a diagnosis tumbling from a doctor’s lips.

It’s interesting to know what causes the sky to appear blue, and the practice of Zen does not demand that we reject scientific or other scholarly pursuits. As valuable as that type of knowledge is, though, it’s no substitute for looking up in wonder at the dome of the heavens and feeling first-hand our connection with every facet of this infinite, breathtaking Universe.

It’s no substitute for the experience of breaking open, dropping away, until there is only sky.

Fayan was going on pilgrimage.

Dizang said, “Where are you going?”

Fayan said, “Around on pilgrimage.”

Dizang said, “What is the purpose of pilgrimage?”

Fayan said: “I don’t know.”

Dizang said, “Not knowing is most intimate.”