Book of Serenity, Case 94

Book of Serenity, Case 94

When Dongshan was unwell, a monk asked, “You are ill, teacher, but is there anyone who is not ill?”

Dongshan said, “There is.”

The monk said, “Does the one who is not ill look after you?”

Dongshan said, “I have the opportunity to look after him.”

The monk said, “How is it when you look after him?”

Dongshan said, “Then I don’t see that he has any illness.”

Last week, Peter Wohl shared some of the most basic Buddhist teachings with us, the life story of Shakyamuni Buddha and the Four Noble Truths. The Cliff’s Notes version, for those who weren’t here, is that 2,500 years ago in India, a pampered prince named Siddhartha Gautama left his palace in search of a cure for sickness, old age, and death. After years of subjecting himself to increasingly self-destructive ascetic practices, he finally turned his back on them, embracing the Middle Way, and achieved enlightenment, awakening to his true nature while meditating under the Bodhi tree.

For the next 40 years, he attempted to explain his insight to others. His earliest teaching, and the one that forms the basis of all sects of Buddhism around the world, was the Four Noble Truths.

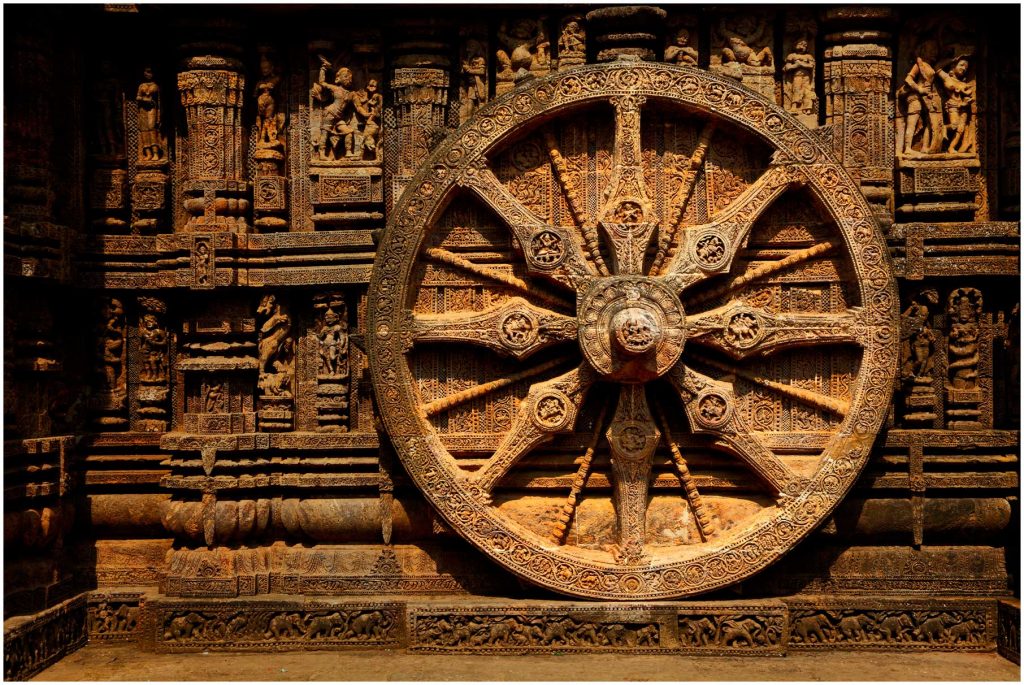

They are, First: There is dukkha. This Pali word, which we usually translate as suffering or stress, carries the connotation of a wheel that has been knocked off its axle. It means we feel off-kilter, out of alignment. It means we’re in for a bumpy, uncomfortable ride. We never have enough of what we want, we jealously guard what we do have so that we never really get to enjoy it, and we’re always getting plenty of what we don’t want.

Second: The cause of suffering is our own clinging and aversion.

Third: There is a way out of suffering. We don’t have to endure it forever.

And fourth: That way out is to ardently train our minds to let go of our clinging and aversion by practicing the Buddha’s Eightfold Path.

Now, I have to confess, when I first began looking seriously into Buddhism, I wanted to call bullshit on these truths. The Buddha’s claim to have found a way out of suffering sounded like a bait and switch to me. From what I could tell, the Buddha hadn’t found an escape from suffering at all. After all, practicing Buddhism has never stopped anyone from getting sick, growing old, or dying. The Buddha himself was among the earliest examples. He died a pretty painful death after eating some spoiled pork at the home of one of his students. Just remember that next time you want to complain about the food during sesshin …

And then there’s Dongshan, in the case I read above. He was renowned as one of the most realized teachers of his time. Hundreds, maybe thousands, of monks traveled from far and wide to practice with him, and he founded our Soto Zen lineage in China, along with his student Caoshan. Yet here he is on his death bed, and he can’t even get any peace because he’s being questioned by the ubiquitous unnamed monk. To anyone keeping score, this koan does not seem like a great advertisement for a path that claims to offer freedom from suffering.

But this kind of skepticism only betrays our ignorance about the true nature of suffering. From a Buddhist perspective, there is a big difference between pain, sickness, or sorrow and suffering. From a Buddhist perspective, pain, sickness, and sorrow aren’t our problem. They’re just sensations. If we don’t allow ourselves to get tangled up in our ideas about how things should be instead, if we don’t become desperate to escape them—so desperate that we make self-destructive choices in our mad scramble to push them away or outrun them—then we don’t actually have to suffer from them. We can open ourselves to experience them with equanimity rather than clinging and aversion.

To some, this may sound as though the Buddha was just peddling stoicism mixed up with some positive psychology mumbo jumbo and repackaged as spirituality, a la The Secret. (Quick, somebody call Oprah and try to line up a merchandizing deal!) But 2,500 years of practitioners know differently. What the Buddha and more than 90 generations of our Dharma ancestors knew from first-hand experience is that each of us, without exception, is so much more than just the scared, confused, self-involved, grasping creatures we encounter in our mirrors.

Beneath all of that clinging and aversion—and the self-centered delusion that drives it—is our Buddha Nature, unclouded, clear, and radiant. This is the “one who is not ill” Dongshan and the unnamed monk are talking about in this case. When we are in touch with this deepest, most essential part of ourselves, then like Dongshan, we don’t see any illness. We only experience the perfection of everything, just as it is. Whether in joy or sorrow, sickness or health, abundance or poverty, even to our dying breath, we know that nothing is ever lacking. This is not some dry philosophical speculation. This is a living truth we can experience for ourselves.

Although our Buddha Nature is always there, waiting for us to manifest it in our lives, we can’t spend a lifetime ignoring it and then expect to be able to tap into it when we’re facing hard times. If we really want to know the one who is not ill, then like Dongshan suggests, we must take the opportunity to look after it.

So how do we do that? Through endless practice. This is the way out promised in the Fourth Noble Truth, the truth of the Eightfold Path, which is a collection of trainings the Buddha recommended to help us get in touch with and care for our innate awakened nature.

Before I share a little about each of the eight parts of the path, it’s important to point out that the Eightfold Path is not an “eight-step program.” We don’t take up the eight parts of this path one at a time with the goal of someday being finished. Rather, we engage in all of them at once, with each part supporting and amplifying the other seven.

The first two parts of the path fall under the category of wisdom. They are Right View and Right Intention.

Those of you who’ve heard there are no creeds or dogmas in Buddhism may be scratching your heads about that first one. But practicing Right View does not mean we have to believe in some set of doctrines, or else we’re condemned as heretics. Right View just means we see ourselves and the world around us clearly. It means we’ve seen first-hand the truth that there is dukkha and that our own clinging and aversion are the cause of dukkha. We don’t have to believe in anything, because we can have a direct personal experience of it. In the parlance of the 12 Steps, Right View would simply be called “admitting we have a problem.”

Without direct knowledge of dukkha, there would be no point in even taking up Buddhist practice. If I don’t see for myself that I suffer, and if I’m not tired of my own suffering, tired of sitting in my own shit, then I’m not going to bother doing the hard work of extricating myself. I’m convinced this is why so many curious people come to visit Treetop and never come back. A lot of them just don’t see the point.

Which brings us to the second fold in the path. Once we know that we’re suffering and we understand why, we resolve to do whatever we need to do to get free. This is what Right Intention means. Right Intention is mustering up the energy and commitment we need to fully engage in Buddhist practice.

The next three parts of the path—Right Speech, Right Action and Right Livelihood—are concerned with ethical conduct. This might be news to those who try to sum up Buddhism as just “staying in the now,” but nearly half of the Eightfold Path is concerned with how we conduct ourselves in the world and in our interactions with other beings. That’s because the Buddha recognized that everyone and everything in the Universe is interconnected. It’s not possible to wake up to our True Nature if we’re continually sowing seeds of suffering everywhere we go. Those seeds will eventually come to fruit in our own lives.

In Soto Zen Buddhism, we practice Right Speech and Right Action by the taking up the 16 Bodhisattva Precepts. These are not external commandments placed on us by some omniscient creator, but a set of trainings we willingly take up because, together, they point the way to awakened activity in the world. Or, as I often like to say, because it rhymes: They’re tools not rules. By practicing ethical conduct, we act as awakened beings even when we’re not particularly feeling it. We don’t follow the precepts because we’re afraid of going to hell, but because we know that if we don’t follow the precepts, we contribute to creating hell on Earth.

Right Livelihood adds another layer to our understanding of ethical conduct. That the Buddha included an entire fold in the path just for our working lives means he believed it is important to think about the wider implications of how we make, and spend, our money. Even if we could follow the precepts to the letter in our daily actions, it would not be possible to live as an awakened being if we remain entrenched in denial about how our labor impacts the world around us. How can we have a peaceful heart if we’re involved in enterprises that harm other beings?

The last three parts of the path fall under the category of mental discipline. They are Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, and Right Concentration. Together, they help us to cut through self-centered delusion and see clearly.

Right Effort means we take the energy generated from our Right Intention and put it to work. The Buddha defined Right Effort as making an earnest attempt to extinguish unwholesome states of mind—particularly the three poisons of greed, anger and ignorance—when we see they have arisen in us; working to prevent them from arising before they do; and striving to cultivate and strengthen wholesome states of mind—such as generosity, lovingkindness, and wisdom—in their place.

So how do we know when greed, anger, and ignorance have arisen, or are threatening to arise, in us? That’s where Right Mindfulness comes in. Right Mindfulness means paying attention. These days, there is a lot of hype about mindfulness, which means a lot of people know just enough about it to be dangerous. The conventional contemporary understanding of mindfulness is that we try to pay very close attention to everything we do, whether it’s eating or doing the dishes—mostly things in the kitchen, it seems like—so that we don’t miss a moment of our miraculous lives. While that may be an admirable goal, as Peter has pointed out, if we’re not careful this understanding of mindfulness can result in greater separation between us and our lives, creating a watcher and that which is watched.

When the Buddha spoke of mindfulness, though, he meant something much more specific than simply staying “in the now.” (That reminds me of the time, a few years ago, when a group of us from Treetop went to see Bernie Glassman, our living ancestor in the Dharma, speak in Portland. Someone asked him, “How can I be here now?” To which Bernie replied, deadpan, “Would anyone who is not here now please raise your hand?”).

Anyway … When the Buddha talked about mindfulness, he was talking specifically about paying attention to ourselves—how we’re feeling, physically and emotionally, what were thinking, what we’re noticing. And the reason the Buddha recommended we pay attention to what’s going on with ourselves is so we won’t be caught off guard. If we can stay aware of the sensation of anger, for instance, rising in us—if we can stay with that tightness in our chest and our stomach, the tension in our brow and our jaw, the quickening of our pulse—instead of with whatever story we’re trying to tell ourselves about whose fault it is we’re angry and what we need to do about it to feel better, then we’re able to stay in the drivers’ seat of our actions. We won’t find ourselves blowing up and saying or doing something we’ll regret before we even know what happened.

But that’s not easy. So we need to cultivate that habit through Right Concentration, or meditation. This is zazen, the central practice of Zen Buddhism. The word Zen actually comes from the Pali word dhyana, which means meditative absorption. In zazen, we sit upright, enacting and embodying Buddha’s awakening under the Bodhi tree in our very posture. Then, as the Japanese Zen teacher Kosho Uchiyama put it, we open the hand of thought, practicing letting go in each moment. Thoughts come and thoughts go, and we simply let them pass like clouds in the sky without chasing after them or pushing them away. In this way, we learn not to identify with our thoughts, not to be pushed around or deceived by them. Over time, we realize we don’t have to take them, or ourselves, so seriously.

In his “Universally Recommended Instructions for Zazen,” Eihei Dogen, the Japanese founder of our Soto tradition called this practice “the dharma gate of joyful ease, the practice realization of totally culminated enlightenment” and recommended that we “learn to take the backward step that turns the light and shines it inward. Body and mind of themselves will drop away, and your original face will manifest. If you want to realize such, get to work on such right now.”

“Body and mind of themselves will drop away, and your original face will manifest.” This is the face of the one who is not ill, the one who does not suffer. We can see that original face, but we must be willing to do the work. We must be willing to look after it.

Too often, in some of the sexier books about Zen, this realization, this dropping away of body and mind and the emergence of our original face, can sound like some kind of spiritual jackpot. If we just keep pumping quarters into the meditation slot machine, someday we might hit it big.

But from my perspective, this way of looking at it is terribly misguided. Awakening is not a thing that just happens to us, like getting shit on by a seagull or hit by a bus. Awakening is a choice we make in every moment. Every instant of every day, we have the opportunity to decide whether we want to nourish and sustain suffering, misery and despair or if we want to look after the one who is not ill.

So, I ask you, along with Mary Oliver, “Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?”

When Dongshan was unwell, a monk asked, “You are ill, teacher, but is there anyone who is not ill?”

Dongshan said, “There is.”

The monk said, “Does the one who is not ill look after you?”

Dongshan said, “I have the opportunity to look after him.”

The monk said, “How is it when you look after him?”

Dongshan said, “Then I don’t see that he has any illness.”

Tears of joy streaming down my face….thank you Jaime !

Wonderful Jaime, I can’t beleive it took me this long to read it. You are really funny. Je t’aime!!!