Probably all human beings spend a lot of time and energy trying to keep their lives under control, but I think we Americans are particularly obsessed with it. We do everything we possibly can to prevent any kind of accident or unpleasant experience. There is a whole mail order catalog full of things to keep life safe: fool-proof burglar preventions, ladders to hang out of windows in case of fire, “the club” to prevent our cars from being stolen. We have warning labels on everything. On ladders, warning us that we could get hurt if we fall off. On candles, warning us that the curtains could catch on fire if we light candles near them. And we have insurance for every possible disaster: health insurance (if we can afford it, that is), mortgage insurance, life insurance, credit-card insurance. You name it. If it can be insured, it will be.

Probably all human beings spend a lot of time and energy trying to keep their lives under control, but I think we Americans are particularly obsessed with it. We do everything we possibly can to prevent any kind of accident or unpleasant experience. There is a whole mail order catalog full of things to keep life safe: fool-proof burglar preventions, ladders to hang out of windows in case of fire, “the club” to prevent our cars from being stolen. We have warning labels on everything. On ladders, warning us that we could get hurt if we fall off. On candles, warning us that the curtains could catch on fire if we light candles near them. And we have insurance for every possible disaster: health insurance (if we can afford it, that is), mortgage insurance, life insurance, credit-card insurance. You name it. If it can be insured, it will be.

We want our lives to be predictable. To be exactly how we planned them. We want to get the best education that we can afford, marry the best person we can find, live in comfortable homes in a good neighborhood, have well-paying, interesting jobs. We want beautiful, healthy children. We want to be healthy ourselves, and live long and satisfying lives. We want to avert any disruption of our plans, to prevent any disaster from befalling us, and we will go to great lengths and considerable expense to do so. We think we have everything all figured out, all the bases covered. We fear the unplanned, the unexpected. In short, we are terrified that life may not go as we wish, that all of our plans and hopes and dreams might be turned upside-down.

Here are the stories of two people who felt just like that. They had careers and understood life. They had their lives planned out. The first is a Chinese story in the famous koan collection The Gateless Gate. It is an unusually rich and deep koan, which doesn’t make much sense without knowing a bit of the history of this story. The great master Bodhidharma brought Zen from India to China in about 500 C.E. He is known as the First (Chinese) Patriarch. The sixth in succession from him was Hui Neng (Eno, in Japanese), the Sixth Patriarch, one of the great figures of Chinese Zen. Hui Neng was an illiterate woodcutter who had a profound enlightenment experience on hearing a man recite a line from the Diamond Sutra. Hui Neng asked the man where he had learned this and was told from Hung Jen (Obai in Japanese). So Hui Neng went to study with Hung Jen, who recognized immediately what deep insight he had. Perhaps to protect him, or perhaps to test his determination, Hung Jen asked Hui Neng to work in the rice mill, polishing rice, a very lowly job, which he did. Somewhat later, Hung Jen chose to give him Dharma transmission, empowering him as a teacher. He gave Hui Neng his own robe and eating bowls, symbols of the teaching authority, of the presence of the Dharma or Truth. But he did this at midnight, in secret, so that none of the other monks in the monastery knew about it. Then Hung Jen told Hui Neng that his life was in danger and he would have to flee the monastery. Hui Neng left that night.

The next morning, when it was time for Hung Jen to give his customary talk, he said, “Today there will be no talk. The Dharma has left the monastery.” The monks wondered what that meant, but then they realized that Hui Neng was gone. They took off in pursuit of him, thinking that Hui Neng had stolen Hung Jen’s robe. Monk Myo had been an army general before he entered the monastery. He was the fleetest runner of the monks, and it was he who caught up with Hui Neng. And this is where our koan begins.

The Gateless Gate, Case 23: “Think Neither Good Nor Evil”:

The Sixth Patriarch was once pursued by Monk Myo as far as Mount Daiyu. The patriarch, seeing Myo coming, laid the robe and bowl on a rock and said, “This robe represents the faith. How can it be competed for by force? I will allow you to take it away.”

Myo tried to lift it up, but it was as immovable as a mountain. Terrified and trembling with awe, he said, “I came for the Dharma, not the robe. I beg you, please reveal it to me.”

The patriarch said, “Think neither good nor evil. At that very moment, what is the primal face of Monk Myo?” In that instant, Myo suddenly attained deep realization, and his whole body was covered with sweat. In tears, he bowed and said, “Besides the secret words and secret meaning you have just now revealed to me, is there anything else deeper yet?”

The patriarch said, “What I have now preached to you is no secret at all. If you reflect on your own true face, the secret will be found in yourself.”

Myo said, “Though I have been at Obai with the other monks, I have never realized what my true self is. Now, thanks to your instruction, I know it is like a man who drinks water and knows for himself whether it is cold or warm. Now you, lay brother, are my master.” The patriarch said, “If that is the way you feel, let us both have Obai for our master. Be mindful and hold fast to what you have realized.”

The second is a very short story, recorded in three of the Gospels. Here is Matthew’s version:

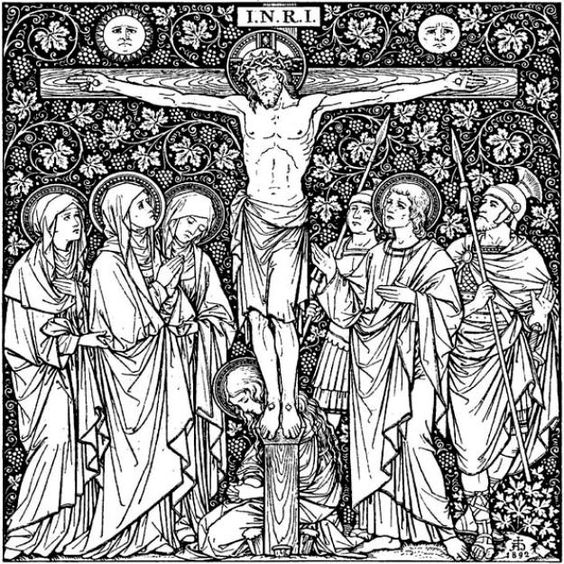

From the sixth hour until the ninth hour darkness came over all the land…About the ninth hour Jesus cried out in a loud voice, “Eloi, Eloi, lama sabachthani?”–which means, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”… And when Jesus had cried out again in a loud voice, he gave up his spirit. At that moment the curtain of the temple was torn in two from top to bottom. The earth shook and the rocks split…When the centurion and those with him who were guarding Jesus saw the earthquake and all that had happened, they were terrified, and exclaimed, “Surely he was the Son of God!”

Both of these stories are about career military men, who often are good planners. They both thought they understood life. They both knew what was what.

Myo had made a career as a general, and had perhaps retired to the monastery to spend his days meditating. He understood how things should go in the monastery. When it was time for the old abbot to step down, the mantle should be passed to the most senior monk, who had dedicated years, perhaps his whole life, to studying Zen. The senior monk was a man of letters, who wrote eloquently and spoke movingly. Everyone knew him; he would be a good teacher and a good abbot. There was a young upstart who had recently come to the monastery, an illiterate woodcutter. But no one paid much attention to him. Even the old abbot seemed to ignore him. He had assigned him to work in the rice mill, and seemed to forget about him.

When the abbot announced that the Dharma had left the monastery, and the monks realized that the woodcutter Hui Neng had left, it was obvious that he had run off with the robe. That he had stolen the robe. So Myo took off after him. The robe had to be brought back to the monastery at any cost. It was the most important object in the monastery. The symbol that there was true teaching there. No matter what, Myo would get it back. You could depend on him. He was ready to kill for it, if need be. But he would bring that robe back.

In the Gospel story, we have another military man. A centurion was the commander of a unit of a hundred men, as the title implies. An officer in the Roman army, a Roman citizen. He also knew what was what. From the way this story is written, we can tell that this centurion was in charge of the crucifixion. He may well have been in charge of many crucifixions. Crucifixion was a particularly brutal form of execution, reserved for the most dangerous criminals: the insurgents, the terrorists. It was done publicly to give a warning to any other would-be rebels. Anyone who received this penalty was a seditious, dangerous criminal, deserving of this brutal death. The centurion was only doing his job, maintaining order in the realm. Crucifixion was a necessary part of maintaining peace in the Empire. The centurion probably didn’t think much about it. It was all in a day’s work.

But something happened to each of these men that turned their whole world upside-down. They each had an experience that terrified them. According to the koan, Myo– the mighty general – was terrified and trembling with awe. Matthew tells us that this hardened centurion was terrified. And both of them suddenly saw. Suddenly, in their terror, they recognized the truth.

In the koan story, we are told that Myo had a profound awakening, and it shattered him. He broke out in a sweat, and he burst into tears. And he was a changed man. Formerly, he had seen Hui Neng first as an illiterate nuisance and then as a dangerous enemy. And now he bows done and asks him to be his teacher.

We are not given as much detail about what happened to the centurion, but surely he had a similar experience. He had just put this man to death. A common criminal. All in a day’s work. And suddenly, his world falls apart. His eyes are opened. And he is terrified. He also must have broken out in a sweat and trembled with awe as he said, “Surely this was the Son of God.”

So what do the stories of these two soldiers have to do with us?

As I said at the beginning, we do everything possible to keep our lives orderly, predictable, disaster-free. Yet, in talking with other people and in my own life, I have often found it to be true that it is at those moments when the order breaks down – when our lives fall apart – that we really see. It is especially in moments of profound terror that we open up. We are opened by the fear. Unwillingly, probably. But we have no choice. It opens us.

It is said that the Chinese ideogram for “crisis” also means “opportunity.” When that which we most dread actually happens – the death of a loved one, a diagnosis of cancer, the loss of a job, the end of a marriage – we are vulnerable. If we allow ourselves to be open to that experience, if we take the opportunity that the crisis offers, we can be changed by it.

One friend has told me that when her father died, she had her first – indeed, her only – profound experience of God. Others have mentioned that an unwanted divorce proved to be the most positive experience of their lives.

As many of you know, I worked in an AIDS clinic for a number of years. I had the incredible opportunity to witness how different people dealt with their diagnoses. And how they approached death.

Some – mercifully few – of the patients received it all with great bitterness. They were angry and bitter when they were diagnosed, and some died angry and bitter. They were hard to care for and their families were often torn apart by the experience.

But many of the AIDS patients have told me that getting AIDS was the best thing that ever happened to them. They were terrified that they would be positive for HIV, and at first the diagnosis was received with dread. It seemed like a death sentence. Yet, as they lived with that sentence, their lives were transformed. Suddenly, life became precious; every moment counted. And they were liberated to really live. To savor every event, to cherish every person.

And many of those who died in the early years of the epidemic came to profound acceptance. To deep realizations of God or Truth or Goodness in their lives. They were lovingly able to embrace death when it came. These people were great teachers to me. Being with them in their dignity and joy and humor was a precious experience.

I am not saying that disaster or tragedy are good things, or that we ought to invite them. But we can befriend them. When our lives fall apart, we can choose to ask “Why me?” To become depressed or despairing. We can rail against our fate and fight it. Or we can choose to embrace the opportunity. To allow ourselves to be changed by the experience. To experience the fullness of life, which includes death and mourning as well as birth and joy. Sickness and pain, as well as health and well-being.

If we can let go of the need to control our lives; if we accept that life is unpredictable, that our hopes and plans can and will be dashed and that our lives can and will be turned upside-down from time to time, then we are free to rejoice in that unpredictability. We are open to learning from the disaster that has befallen. Our lives will be infinitely richer for it. And who knows what may come of it?

To return to our two soldiers: For each of them, everything we know about them is contained in these very short fragments. These few short paragraphs are all we know of Monk Myo. For the centurion, all we have is this one sentence. The rest of their lives are total mystery.

What happened to them, do you think? Monk Myo’s future probably was to return to his teacher, Hung Jen, who would have recognized the change. Most likely, after some years of maturing of his enlightenment experience, he would have gone on to be given Dharma transmission himself. To himself become a teacher.

But that centurion. His whole life was being an officer in the military. And his job was executing criminals. What must have happened to him? How do you think his life was changed?