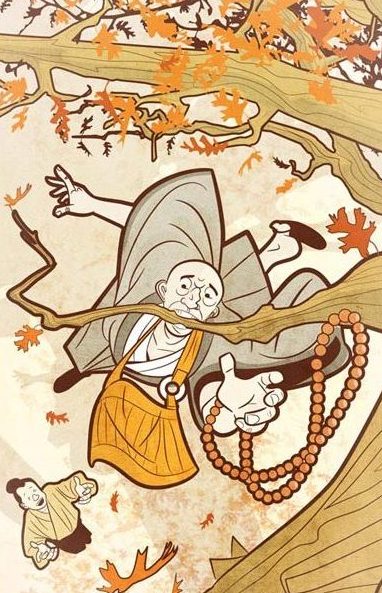

Art by Mark Morse

Gateless Gate, Case 5

Kyogen said, “Its like a man up in a tree, hanging from a branch with his mouth; his hands can’t grasp a bough, his feet won’t reach one. Under the tree there is another man, who asks him the meaning of Bodhidharma’s coming from the west. If he doesn’t answer, he evades his duty. If he answers, he will lose his life. What should he do?

What does it mean to be up the tree like the person Kyogen is speaking about? If we respond to the question we will fall and probably die. However, if we do not speak, we ignore the questioner and fail in our responsibility to the Dharma. Does this seem like an absurd dilemma the Master has created for us? Perhaps, and yet it can be understood in such a way that it’s remarkably relevant to our lives today.

Why is this man clinging to the branch? Because he does not want to fall. He does not want to die as he meets the ground below. However he is clinging to an illusion, the illusion that death can be indefinitely avoided or averted. Eventually he and every one of us will crash, passing into oblivion. It is inevitable, not matter how healthy and strong any of us living up the tree are, eventually our jaws will tire and our grip will fail. Yet we live our lives as if that will never happen. And what is the price of that avoidance of death for this man and for all of us as well? His life is spent clinging by his teeth to the branch. He is unable to speak, to teach, to express and manifest the Dharma. He lives and yet he misses all of life by clinging and vainly trying to preserve life.

To be truly alive we must be willing to let go, to enter free fall. And we must be willing to speak and manifest the truth as we know it, on our way down. We must work to fulfill the Bodhisattva vow to free all creations, using however many moments we have available before we meet our end. As Zen Buddhists following the Mahayana path of the Bodhisattva, we have an imperative to enter deeply into the midst of this crazy world of samsara, acting quickly and decisively in harmony with the Dharma. Life doesn’t wait for us and we can’t afford to sit on the sidelines let it pass us by.

As the Evening Gatha says:

“Let me respectfully remind you

Life and death are of supreme importance

Time swiftly passes and opportunity is lost

Each of us must strive to awaken; Awaken!

Take heed; do not squander your life.”

Do not squander your life. Mary Oliver asks us, what will we do with this “one wild and precious life”? We must not spend our precious days clinging to a branch. We need to let go and live, that is Zen! That is our heritage, we are the descendants of courageous women and men whose responses were like lightening, meeting in each moment without hesitation, with absolute conviction and with total commitment. Women and men who saw that their responsibilities as Bodhisattvas, as bearers of a Dharma, which they used to determine their actions in each and every moment.

It appears to me that in this day and age that has changed. We Zen Buddhists have become very cautious and deliberate. We hesitate to act. We want to sit and carefully contemplate whatever question is at hand. We want to thoroughly debate each matter, considering all of our options and all of the possible outcomes before we act. For some reason we have come to believe that is the way of Zen.

Of course, knowing all options and choices and predicting all possible outcomes is almost always impossible. We are often functioning within highly complex chaotic systems, which present an infinite number of variables, offering endless possible combinations. Our most educated guesses are only guesses and yet we cling to the delusion that we can predict outcomes with some degree of certainty.

The consequence is that many of us in Zen today find ourselves unable to act. It is as if the man up the tree wants to make a careful and deliberate analysis of whether or not his words will be effective before he lets go. How will they be received? Will the questioner be receptive and benefit in a definitive way, making his sacrifice worthwhile? Or will he ignore the teaching he receives making the respondent’s death in vain? Will his death be quick, or will he suffer when he reaches the ground? And so, following an endless chain of questions and finding them unanswerable, he remains there clinging to both the branch and to the delusion that by not choosing, by not acting, he is safe.

In the past couple of months, three of the world’s most prominent religious leaders, Pope Francis, Patriarch Bartholomew, the leader of the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Dalai Lama have all made groundbreaking statements on behalf of our world and its people. It is clear to them and to me that the fate of the world requires action now. Indifference to environmental devastation, the worsening fate of the poor while the rich continue to amass incalculable fortunes and the senseless violence and war all over our globe cannot be allowed to continue unabated, without the all of humanity, and all of the beings that inhabit this planet with us, facing dire consequences.

Still we sink our teeth deeper into the branch. The problems seem too overwhelming and we appear to be powerless in the face of the enormous forces allied on the side of destruction and profound indifference of many others. How can we make a difference? We become paralyzed with angst and avoidance. Denial, rationalization and numbing out seem to be our only alternatives. As we cling the branch we seek distractions to make the untenable nature of our situation go away. For example, we delude ourselves into believing that material possessions can end the great discontentment that we feel.

On those occasions when we are inescapably confronted with the reality of the situation, we tend to focus on blaming others: the rich, the politicians, the banks, the multi-national corporations, the oil companies, the powerful influence lobbies, the military industrial complex are all to blame. What can we do? Yet the truth is that we are the powerful ones, we just don’t see our own power. All of those entities work for us, they rely us giving them our money and on our being frightened, overwhelmed and falling into a stupor rather than fostering change. We support their destruction with our dollars, we support them with our labor, we support them with our failure to take action, and we support them with the bodies and lives of our sons and daughters who go to fight in the endless series of insane wars.

Like petulant children we demand an endless supply of oil and petroleum products. The tankers are sailing for us, so we can’t blame the oil companies. That same hunger for oil furthers the destabilization of the Middle East and keeps us involved in the endless conflicts there. We can’t blame Congress or the military. They are keeping the pipelines open for us. We have the blood of many brave and dedicated young men and women on our hands.

There is another very famous koan that addresses this same question of action versus paralysis driven by fear, uncertainty and doubt. In that koan, Nanchuan comes upon the monks of the eastern and western halls arguing about a cat. He picks up the cat and takes out a sword. He then says that if the monks can say a word and he will spare the cat, however if they don’t, he will kill the cat. No one speaks or acts, so Nanchuan kills the cat. Later Chao Chou returns and hears about the incident. Chao Chou places his sandals on his head and walks away. Nanchuan tells Chao Chou that if he had been there, the cat would have been spared.

What prevented the monks from speaking or acting spontaneously as Chao Chou did. Some may have been afraid to look foolish, others were unsure about what the right thing was to say, some may have been trying to think of something clever and very “Zen” to impress the teacher and their fellow students. The very monks who were just loudly debating some obscure and probably completely inconsequential point, couldn’t summon up the slightest gesture when life and death were at stake.

And what of Chao Chou’s act of putting his sandals on his head as he walked off? That gesture was a sign of mourning in China at that time. Chao Chou’s instantaneous response was completely appropriate to the circumstances, precisely because he did not allow complex reasoning or abstruse arguments to obstruct his action. Chao Chou didn’t obsess about whether or not his response was the right one or the best one, or worry about what others might think of it. He acted without hesitation and with complete commitment. That is true Zen, true courage, and true freedom.

Today young men and women of color are being killed because of prejudice and hatred. Peaceful Christians are slaughtered in their place of worship because of the same hatred. The next victims of this uncontrolled brutality can’t wait for us to form committees and endlessly debate whether or not we should respond. The hundreds of thousands of young women being raped on our college campuses and in our communities need us to stand up now to make it perfectly clear that all violence against women is absolutely unacceptable. We must get our soldiers home and assure our veterans the care they deserve. With every day that we don’t act, more of our soldiers, more innocent civilians and more people whose greatest crime is a desire to defend their homeland, will die.

One estimate is that 27,000 species are lost each year and at the present rate, 22% of the species on earth will have been lost by 2022. How many more extinctions will occur while we contemplate the pros and cons of taking action? 15.8 million children in the US live in households where they don’t receive adequate nutrition. Should we explain to them that there is nothing we can do, that the problems are too large, and that we don’t have any answers?

Do these realities depress us? Do they make us feel impotent and overwhelmed? If we allow ourselves to sink into the calculus that conventional logic offers, our cause is hopeless. But, if we act, just act, can we break free from the stranglehold of despair and start to make a difference. Can we just open our mouths, release the branch and enter the freefall of the unknown and the unknowing?

But if we do decide to let go and act, then what should we do? What is the correct action? My answer is that all action is correct action. The only way that we can be fail is to follow the example of the man up the tree and the monks in Nanchuan’s monastery and do nothing. I believe that had they done almost anything in response, Nanchuan would have spared the cat.

If we see a child about to be hit by a car, do we stop to consider all of our options or do we rush in to pull them to safety? When life and death are involved and there is great urgency, we respond instinctively. In our world today, life and death are very much involved on an unprecedented scale and the urgency is clear. We must wake up, we must see the truth that is before our eyes, and we must act. It we act from a place of spontaneity and genuine compassion, then like Chao Chou we will act in a way that is appropriate to the circumstances and the whole world will change. Let’s open our mouths, fall together and make a difference for this world on the way down!

Kyogen said, “Its like a man up in a tree, hanging from a branch with his mouth; his hands can’t grasp a bough, his feet won’t reach one. Under the tree there is another man, who asks him the meaning of Bodhidharma’s coming from the west. If he doesn’t answer, he evades his duty. If he answers, he will lose his life. What should he do?

Almost five years later, I’m first to comment? Thank you for the kick in the pants. _/!\_